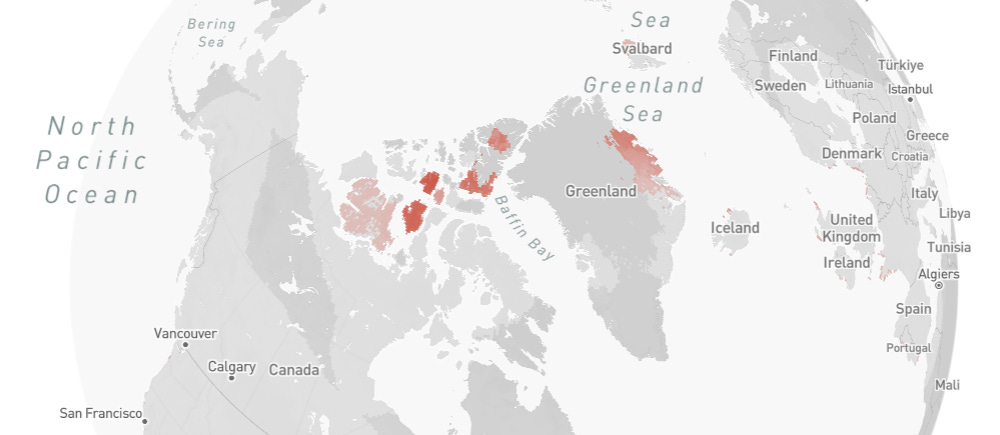

Born in the land of the midnight sun on the edge of the Arctic Ocean is a unique group of birds. Emanating from the North Slope of Alaska to the tundra of Canada, Greenland, Scandinavia, and Russia, they fly south and scurry in front of our bare feet at the beach. Most people know them as sandpipers or shorebirds.

In his famous book, Peter Matthiessen called them the Wind Birds. Though representing only a few dozen of the world’s 11,000 bird species, they migrate as far as any. The adults arrive on the breeding grounds at the end of May and immediately set about finding a mate, defending a territory, laying eggs, and raising young. The pace is frenetic. Though these birds are born there and raise future generations there, it is only home for a few weeks or months. Most of the year, they are elsewhere, often five to ten thousand miles away. Few other birds fly so far for such a short stay. For shorebirds, the Arctic tundra is worth it, teeming with insects to feed their chicks.

By mid to late June, the adult males are already heading south – “fall migration” – and are arriving in California or Delaware. They are followed in July by the females, leaving the young ones alone to enjoy the last the tundra has to offer as the Arctic summer fades. By August, the juveniles, guided by internal and external constellations of instinct, stars, magnetospheres, and other unseen clues, follow their long-gone parents. They join them along the coasts of the US or southern Canada, or Central America. Some will spend the winter – September thru April – on the plains of Argentina or coasts of Australia.

Not all of them are Arctic breeders. A few target the subarctic or boreal forests of Alaska and Canada. And a few more – avocets, stilts, Snowy and Piping Plovers, Marbled Godwits, and Willets, nest near inland water bodies across the American West or along nearby coasts.

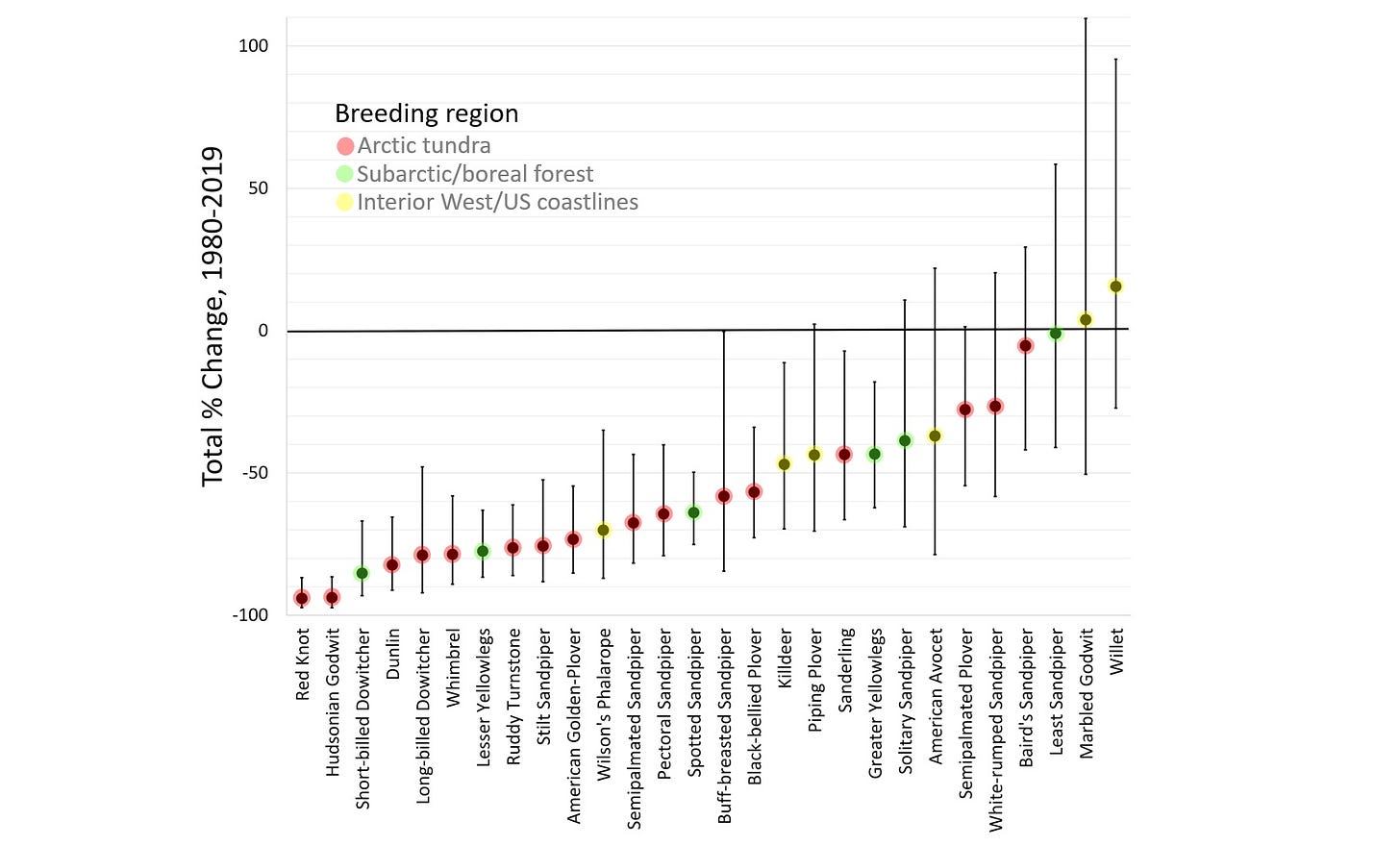

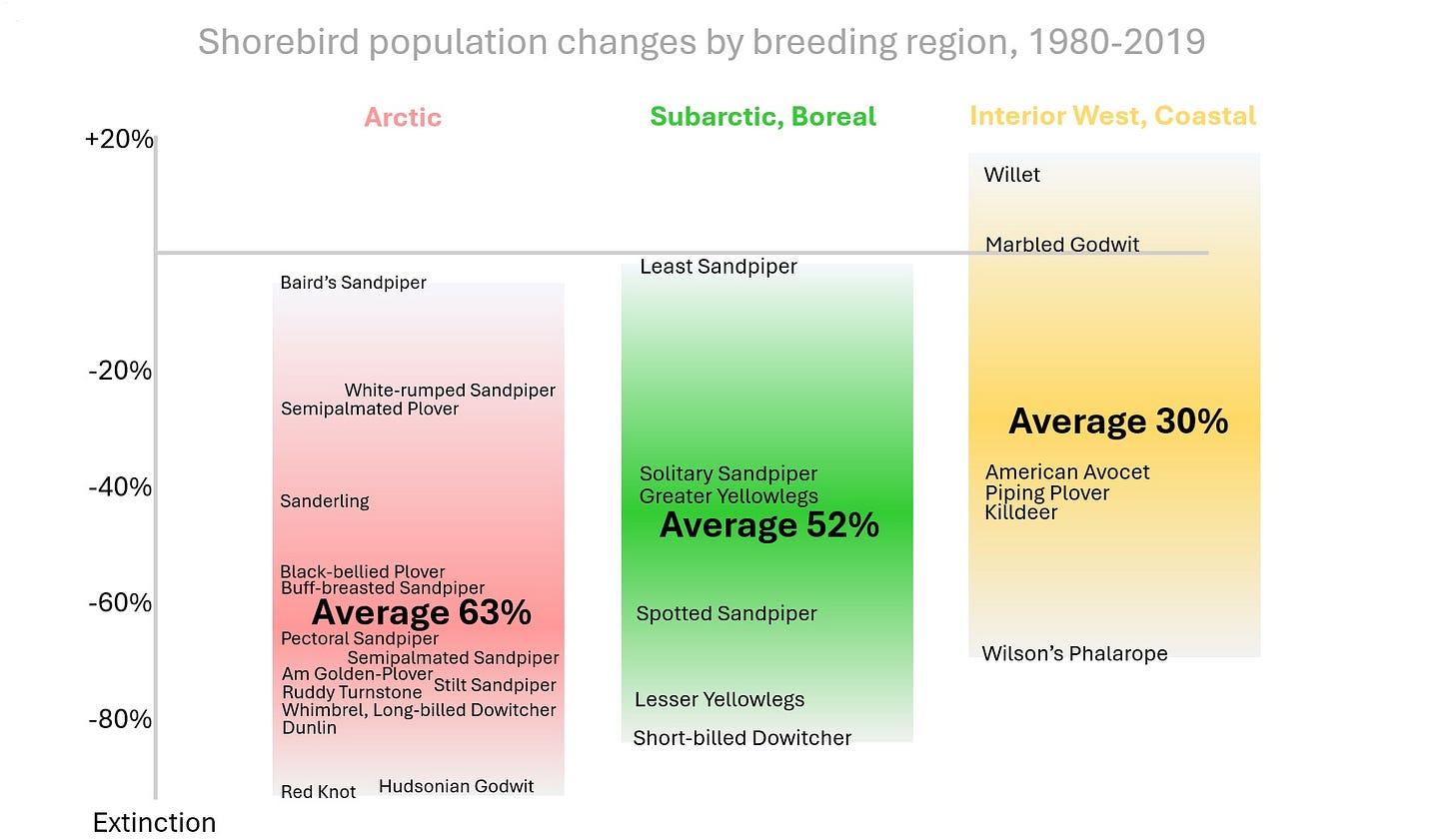

But nearly all of them are declining precipitously. A 2023 study by Smith et al looked at data from 28 species over forty years, from 1980 to 2019. The surveys – 82,843 of them spanning 668 sites – were conducted during fall migration, were at migration stopover or wintering sites in central and eastern North America, with few West Coast sites. They found that all but two species had declined, and most – 24 of the 28 – had declined more than 25%. Sixteen of them, still more than half, had lost 57% to 94% of their populations. Moreover, they found that, for most species, the declines were accelerating in recent years.

Smith et al. only briefly discuss possible reasons for the declines, but give no definitive answer. Imagine a flock of migrating Red Knots or Hudsonian Godwits descending through the coastal clouds and beach haze of a favorite stopover spot, where they can rest and refuel for the next thousand-mile leg, only to find their prey diminished or the habitat completely gone, flooded by the construction of a seawall or filled and converted into a parking lot. Or imagine the Arctic tundra home of Dunlin, Red Phalaropes, and Pectoral, Semipalmated and White-rumped Sandpipers reduced to desert-like conditions by the trampling of Snow Geese, whose populations doubled every few years with the greening of the Arctic under 4C of climate change. All of these things have happened.

It’s pretty clear from their data that Arctic breeders are declining the most.

Indeed, a temperature increase of 4C is on par with some of the largest mass extinction events the earth has ever seen. What is going on up there? While logistics make it difficult to study fledging rates and juvenile survival across such a vast and remote region, we do know that the Arctic is changing dramatically.

Flowers are fruiting one to two weeks earlier, and first insect hatches are generally following suit. Willows are marching down from the Brooks Range, colonizing the tundra. The entire region is in flux.

For shorebirds, they are likely experiencing phenological mismatch – a timing problem – between when the insects are hatching and when their chicks are need to fatten up. Shorebirds are not really migrating earlier. Their migration timing appears more hard-wired to the sun – to day length - than to the weather. Date of first egg laying has moved up only a few days, hardly keeping pace with the insects. By the time the shorebird eggs hatch, the insect boom may be fading. The sandpipers have thus traveled nine thousand miles for a smorgasbord, only to arrive and discover that the meal time was moved up, they never got the memo, and only crumbs are left.

Another recent paper, by Anderson et al. (2023) entitled “Climate-related range shifts in Arctic-breeding seabirds,” focuses on two study sites in the eastern Canadian Arctic, perfectly in line with many of the migrating shorebirds counted by Smith et al. Smith was a co-author in the Anderon paper. Anderson et al. found that Arctic shorebirds are shifting their breeding areas as the climate warms. Focusing on twelve Arctic nesters, they found that, compared to the 1990s, shorebirds that like it warmer were moving into their study site, while shorebirds that like it cooler were moving out, presumably pushing even further north.

Comparison to eBird trends

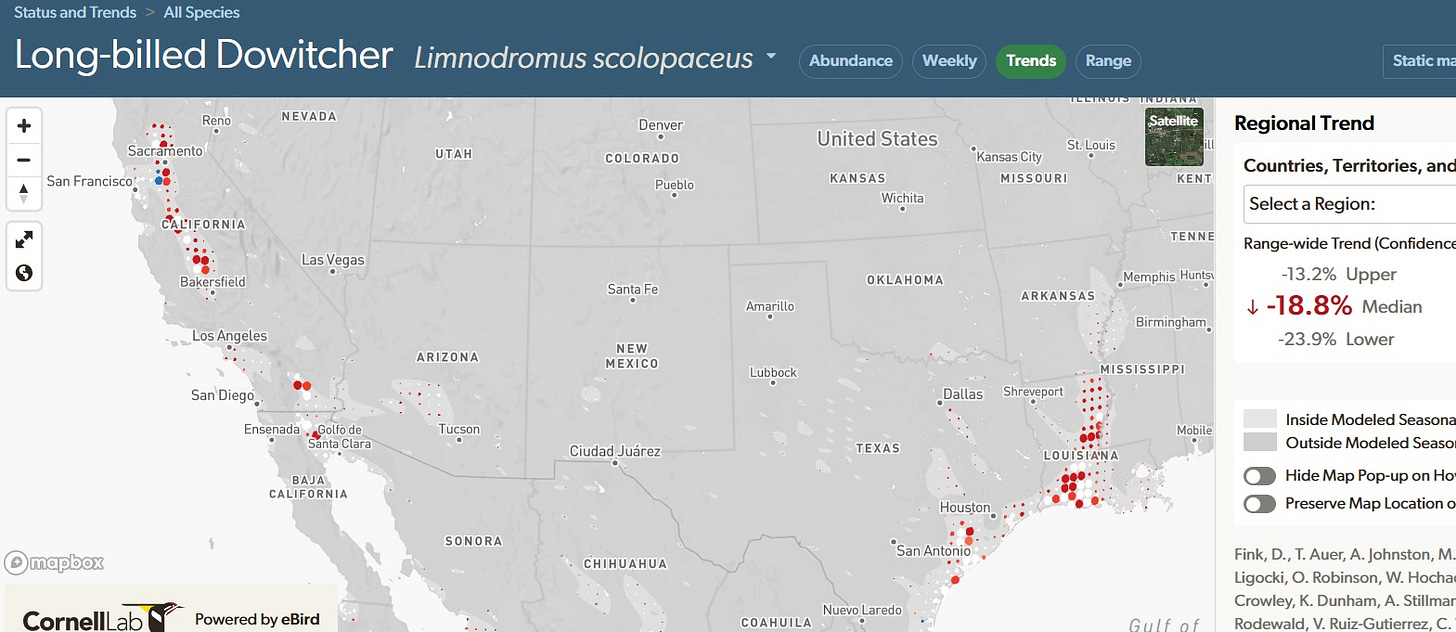

Smith et al. cite many studies – for Red Knots, Ruddy Turnstones, Semipalmated Sandpipers, etc. – that have produced results like theirs. Here I compare their results to eBird’s new trend analysis feature. For shorebirds, this only exists for 16 of the species. It is also only for about ten years, as opposed to the forty-year period covered by Smith et al. For comparison, I converted all the rates of change to annual rates.

For all but three species, Smith et al. show steeper declines. This is likely because the Smith surveys tracked abundance – the number of birds seen. eBird trends are based on frequency, meaning presence/absence. Thus, if there were ten survey sites (or eBird hotspots) visited by Long-billed Dowitchers and, over time, the dowitcher numbers fell 2% per year, but they were still present – just in lower numbers – at each site, eBird would detect no change, while Smith’s abundance surveys would ideally reflect the 2% annual decline. Thus, eBird could potentially underestimate such a change, though they do mitigate this by breaking up their analysis into small increments – each hotspot is essentially a study site - which should catch more locations where the bird is not detected and thus impact frequency.

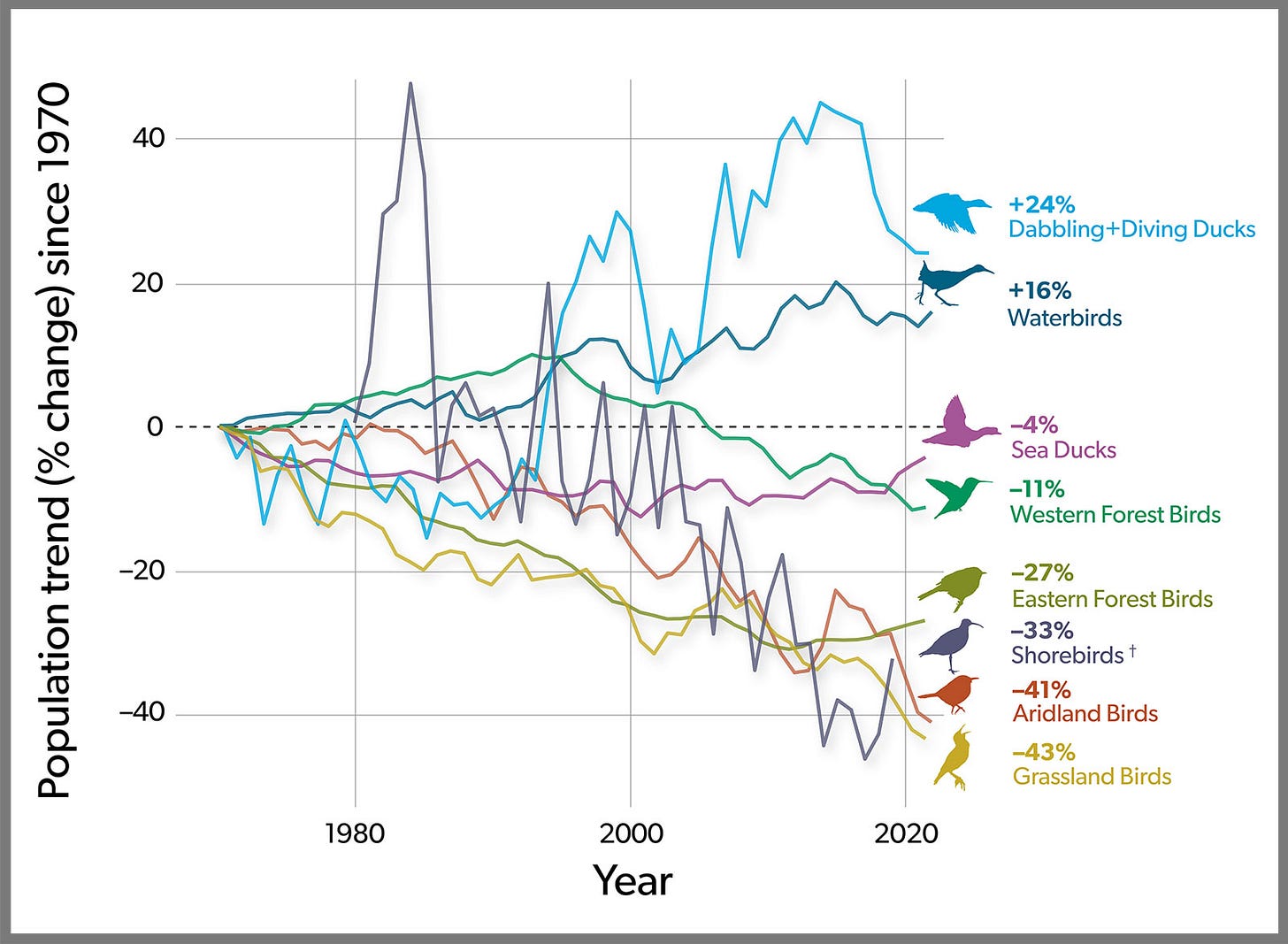

The decline in shorebirds was recently highlighted by 2025 State of the Birds Report, a partnership of conservation initiatives across the US and Canada. In their list of 112 “tipping point species,” shorebirds accounted for 24 of them. Here is the graph in the executive summary.

Thanks for the detailed report, sad though it is. I love the photographs, including those from my birthplace, Port Townsend. We have none of those birds here on Dabob Bay and far fewer of any migratory birds than previously in the 74 years I’ve lived here watching and counting. I am of course intrigued by your description of how the “juveniles, guided by internal and external constellations of instinct, stars, magnetospheres, and other unseen clues, follow their long-gone parents.” Maybe sometime you could post an article just on this.

As per the poem I wrote—three five or seven Does not constitute a flock We’re witnessing insect bird, mammal and predator declines of what was left when they started tracking it in the 50s And who’s to blame? The two legged fucks running this planet