The lynching of Greenpeace

How a small-town jury sought retribution against the Standing Rock water protectors

On March 19, an all-white jury in a small rural courthouse ruled that the environmental activist group, Greenpeace, should pay Energy Transfer Partners (ETP) and Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) $666,890,020. That’s two-thirds of a billion dollars. The majority of that sum was for punitive damages and “defamation of character.”

Standing Rock 2016

If you were at Standing Rock in the fall of 2016, you undoubtedly saw the thousands of people from hundreds of Native nations who converged to support the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. Over 400 tribes wrote official letters of support. Material support came from everywhere. The Pequot brought blankets and warm clothes. Cherokee Nation shipped bottled water. The Tlingit arrived by canoe. And the flags of hundreds of Native nations lined the dirt road into Oceti Sakowin Camp. It became quite possibly the largest gathering of Native Americans in history.

You also saw allies from far and wide, including the impressive arrival of a convoy of US military veterans during a blizzard. And you followed the legal updates from Earthjustice, who continue to work with the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe.

But you probably didn’t notice Greenpeace. They were there, but their presence was small, and, being only non-Native allies (or using Native staff or volunteers), they were not in a leadership role. It was the Lakota, the Oceti Sakowin, who made the final decisions regarding strategy, protest, and prayer. Greenpeace provided support for non-violent training and winterizing camp. Here’s one member’s account.

If you – like me – were not there, but were following closely on-line, riveted to extensive news coverage from Democracy Now and live video feeds Unicorn Riot and Digital Smoke Signals, and reading all the in-depth analysis, you probably never knew Greenpeace was there. I didn’t until this trial made news.

So my first question is: What the hell just happened to Greenpeace? And my quick follow-up is: why them?

Since the events in question took place nearly ten years ago, here’s a quick recap:

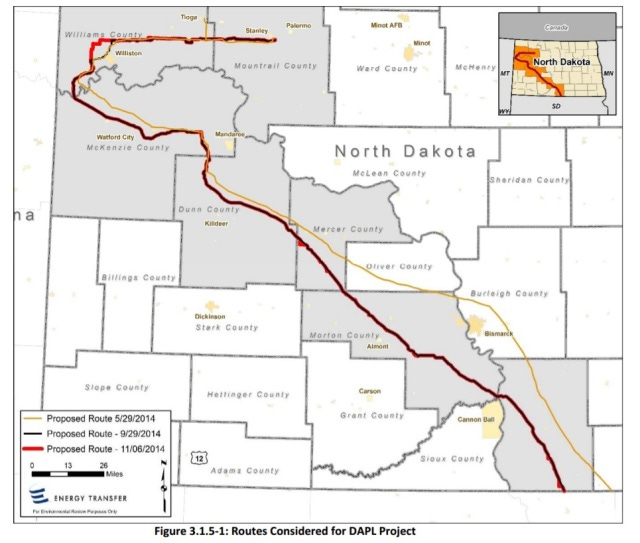

· In 2014, ETP proposed the pipeline to move oil from the Bakken fields to Illinois. The original route (in yellow) ran just upstream of Bismarck, North Dakota.

· Four months later, without any public meetings or tribal consultation, they re-routed it to just upstream of the reservation (the red line). While the new route was just outside the reservation, it was well within unceded lands from the Treaty of 1851, and plowed right through hundreds of cultural sites, including burial areas. It also poses a direct threat to the reservation’s water supply.

· When ETP finally met with the tribe, they promised, “We will re-route as necessary for threatened and endangered species and cultural resources.”

· But ETP ignored the tribe and, in 2016, proceeded to construct the pipeline.

· That summer, some youth from the reservation approached Ladonna Brave Bull Allard for permission to camp on her land to protest the pipeline and protect the water. As news spread across Indian Country, their camp grew into the massive effort to stop the pipeline.

· In December 2016, the Obama administration ordered a halt to the pipeline in order to conduct an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS). It was astounding that this had not already been done, as that is normally a required permitting process for a large project like this. In January, 2017, Trump took office and lifted that requirement.

· Since then, a judge has ruled that an EIS must still be done, but that the pipeline can remain open in the meantime. And that’s where we are today – the pipeline is running, but it still has no final permit. (A Final EIS and is expected this year.)

This case, ETP/DAPL v Greenpeace, is solely focused on the events of fall 2016, the conflict between the water protectors and ETP. ETP was further backed up by law enforcement from Morton County and North Dakota. They were also joined by 67 other police departments, from as far away as the white suburbs of Chicago and New Orleans, all eager to practice their use of recently acquired surplus military equipment. This equipment included cell phone scramblers, tanks, machine guns, and even a missile launcher. ETP also hired the mercenary firm, TigerSwan. Their actions have been extensively covered by The Intercept.

In practice, the most memorable confrontations – widely covered by the media – included the use of attack dogs, water cannons in sub-freezing temperatures, and flash bang grenades fired directly at non-violent protestors at close range.

The Legal Battles

In the aftermath of the conflict, local law enforcement filed criminal charges against approximately 800 individuals. The vast majority saw their charges dismissed.

At the same time, the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe sued the Army Corp of Engineers over the permitting and lack of transparent response plans. That suit remains unresolved.

But ETP wanted to go after the water protectors for civil damages, to send a message. Ever since a similar effort regarding Chevron’s pollution in Ecuador, these kinds of civil suits by large corporations against protestors have gained traction. Called Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation, or SLAPPs, many states consider them a threat to First Amendment rights and have laws restricting them. North Dakota does not.

The legal world of SLAPP suits is quite small. From Ecuador to Standing Rock, many of the same lawyers and law firms have been involved – on both sides. The firms supporting industry have close ties to Trump and other Republican officials. In this case, Gibson Dunn, representing ETP, also represented the Brakeen family in an attempt to overturn the Indian Child Welfare Act. (Check out

’s Season 2 of her podcast, This Land, for more on the connections between Big Oil and legal threats to tribal sovereignty.)Making a civil claim for damages against Democracy Now, as a news organization, or against the tribe, as a government entity, would have made more sense – but would have been more difficult. So ETP went after Greenpeace and several other non-profits in federal court. In February 2019, a judge dismissed their case with prejudice, meaning they could not file it again. He considered it frivolous.

So ETP thought they’d try it in a small town, just like the song says.

They sued Greenpeace for civil damages at the local county courthouse. That’s in Mandan, North Dakota, population 24,000. Morton County, though on unceded lands of the Lakota, is 94% white. Last year, it voted 75% for Trump.

For ETC, this was the equivalent of white sheriffs trying a Black man in a small southern town. The judge and jury shopping mirrored the prosecution of Leonard Peltier in the 70s. There’s a reason why Natives call the Dakotas the Deep North. With Greenpeace, ETP also shopped for a defendant.

Legally, Greenpeace is actually three organizations: Greenpeace Inc., Greenpeace Fund, and Greenpeace International. All three were named in the lawsuit. Because these three entities worked together, they were also charged with conspiracy and found guilty of that.

For the Lakota, it was a not a jury of their peers. The nine-member panel was all white. Furthermore, most of them had ties to the oil industry. They had probably been personally inconvenienced by the conflict, largely because law enforcement closed Highway 1806, one of the main routes south from the county, for several months. And racial conflicts were ubiquitous. Anyone watching Digital Smoke Signals saw local white thugs on snow mobiles repeatedly trying to run Natives off Morton County roads. And the jurors got their water supply from upstream of the pipeline, not downstream, like the Standing Rock Sioux. But the judge dismissed these concerns and also denied a motion to move the trial to another venue.

In closing arguments, ETP’s lawyer accused Greenpeace of being the masterminds of “eco-terrorists,” of taking “a small, disorganized, local issue” and exploiting it to “promote its own selfish agenda,” which is to protect the environment. That a lawyer representing a for-profit oil company, which by definition pursues a profit-maximizing agenda, felt comfortable calling a non-profit that relies on volunteers “selfish” tells us a lot about his assessment of the jury.

The Verdict

The jury didn’t just buy ETP’s argument, they ate it up. ETP had only asked for $300 million. Everything on top of that – the punitive stuff – was purely at the jury’s discretion.

The final verdict awarded the following damages:

· Compensatory damages and interference with business: $163 million

· Punitive damages, defamation, and punitive damages for defamation: $502 million

· Conspiracy (between the three Greenpeace entities): $2 million

On the jury’s 33-page verdict sheet, they were asked questions such as, “How much, in your discretion, do you award in presumed damages for harm to Dakota Access’s reputation?”

In a world with spiraling climate change, it’s hard to imagine what one could say to further tarnish an oil pipeline’s reputation. ETP’s reputation, especially, was already at rock bottom. In 2019, due to an explosion and oil spill in Pennsylvania, it was fined $30 million and banned from obtaining federal permits for future projects (since lifted by Trump).

With DAPL, ETP violated a number of permitting requirements specifically designed to prevent the kind of conflict they created at Standing Rock. I list their trail of broken laws here.

For the Morton County jury, however, oil pipelines have reputations worth protecting. Either that or they were still experiencing white rage euphoria after the election.

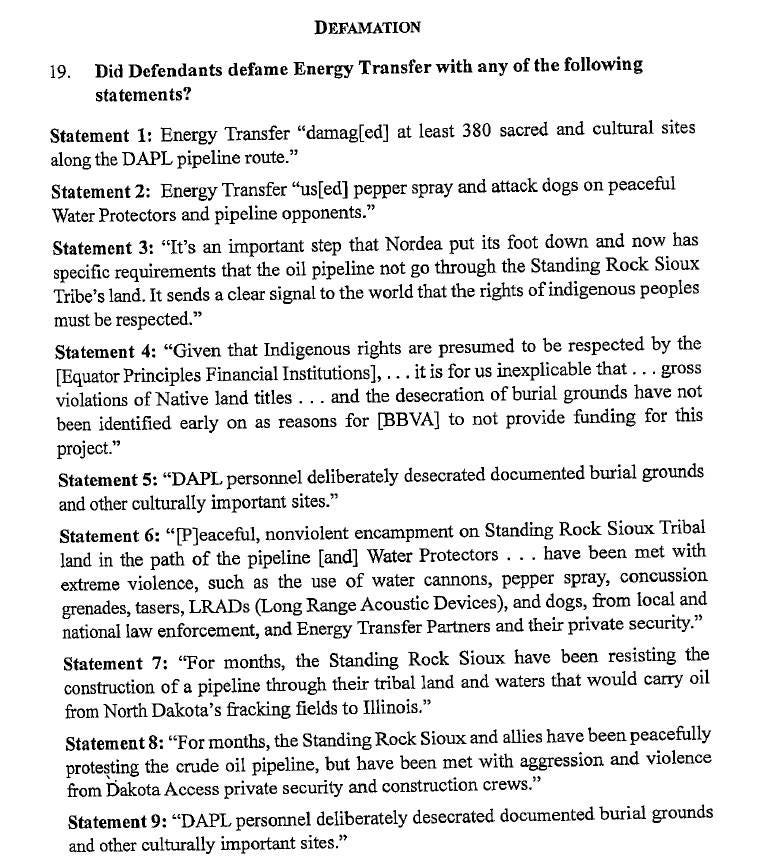

The defamation charge was quite specific. The jury was asked to evaluate nine statements by Greenpeace, and to award damages for each statement specifically, if they found it to be defamatory. Here are the nine statements:

If you followed the Standing Rock conflict, the statements above read like the news. We saw these things happen in real time, such that these statements could have been made by anybody watching. Indeed, I’ve heard such statements – and stronger ones – from dozens of people and organizations. There is video footage backing up every statement. Apparently the jury was watching a different channel; they found all nine to be false and defamatory.

There’s another disturbing aspect to this case. It’s like American politics – it’s white people talking about brown people. It’s ETP and Greenpeace arguing over Lakota sacred sites, burial grounds, Native sovereignty, Indian law, and the nature of unceded lands – things that white people, even white allies, typically don’t understand. Like so much American dialogue about people of color, it’s white people doing all the talking.

After the Verdict

The reaction of the Standing Rock Sioux was predictable. Greenpeace? What? Who? We did it. We stood up.

Janet Alkire, current chairwoman of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, issued this statement on the tribe’s website:

“Energy Transfer’s claims in this case were ridiculous. They were wholly disrespectful of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, our ancestors, and our youth, who started the movement in 2016 to protect our water from an oil spill from DAPL. Neither Greenpeace nor anyone else paid or persuaded Standing Rock to oppose DAPL. Our young people and our elders urged us to protect our water and unci makah (grandmother earth). That is what happened, and is happening still. Energy Transfer’s false and self-serving narrative that Greenpeace manipulated Standing Rock into protesting DAPL is patronizing and disrespectful to our people.”

Natali Segovia of Water Protector Legal Collective debriefed the case, “At its core, it’s a proxy war against Indigenous sovereignty using an international environmental organization.” See their website for more details on the case, including a pdf of the jury verdict. Also check out

’ interview of Segovia on The Red Nation Podcast here.For its part, Greenpeace is appealing, which would move the case to Bismarck.

If SLAPP suits are going to stand, I’m imagining a Native claim against the United States. We would ask the jury just two questions:

· In the Declaration of Independence, Indigenous people are referred to as “merciless Indian savages.” Do you find that defamatory?

· If yes – and keeping in mind that this was one of the main justifications for revolting against the British and the subsequent ethnic cleansing of Native Americans – how much, in your discretion, do you award in presumed damages?

The case will be heard in Pine Ridge or Tahlequah or Puyallup or Red Lake. We’ll get the jury ready.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

For my past blog posts about Standing Rock, see this page.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

And, by implication, environmental protest and the will of Native peoples and the preservation of their land.

A colossal travesty