The generals who refused

They walked away from the Trail of Tears

My people know a story about two generals who took a stand. They were sent to deport us, but then sought to protect us, and, in the end, walked away from their assigned mission.

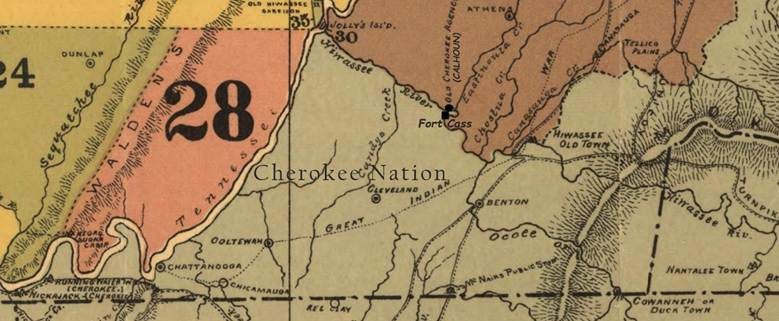

This was in the rolling hills and valleys near today’s Chattanooga, along the Tennessee and Hiwassee Rivers, at a place we used to call Cherokee Nation, our homeland.

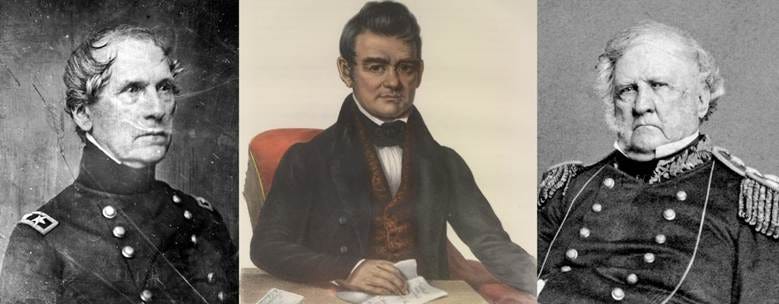

General John Ellis Wool

On the Fourth of July, 1836, General John Ellis Wool reported for duty at Fort Cass, Tennessee. This was to be the US Army’s central command for the “removal” of the Cherokees.

The Indian Removal Act was President Andrew Jackson’s signature legislation. The plan was to ethnically cleanse all the lands east of the Mississippi. Jackson’s Secretary of War – yes, that’s what they called it back then – was Lewis Cass. It was Cass who ordered General Wool to Fort Cass.

(I’ve written about Cass before, how he withheld the smallpox vaccine from the tribes of the northern Plains while he vacationed in Paris.)

Wool’s mission had two prongs:

1) to prepare the Cherokees for imminent deportation, scheduled for May, 1838; and

2) to protect white pioneers from a supposed Cherokee uprising.

At the same time, the Cherokees were asking for federal protection from white pioneers. Just a week before Wool’s arrival, Cherokee leader Major Ridge wrote to President Jackson, explaining that “…the lowest classes of the people are flogging the Cherokees with cowhides, hickories, and clubs. We are not safe in our homes. Our people are assailed day and night by the rabble…. Send regular troops to protect us from these lawless assaults….”

Upon arrival, Wool was deluged with 2,400 local volunteers – white pioneers – who would act as supporting militia, an early version of the National Guard, but with the mission of ICE. Wool considered their numbers far too many. And he didn’t trust them, considering them more of a threat to peace than keepers of it.

Wool met with Cherokee leaders, such as Chief John Ross and my own ancestor Richard Fox Taylor (who would later lead the 11th Detachment on the Trail of Tears). He learned that the 16,000 Cherokees were nearly unanimous in opposition to removal. We explained how it was based on a fraudulent treaty that was only signed by a small minority faction. Wool understood and sympathized.

Indian removal was one of the most contentious issues of the era, bitterly dividing the nation. It was debated in newspapers and in pamphlets handed out in the streets. After fierce debate, Congress approved the Indian Removal Act by five votes, and approved that fraudulent treaty – the Treaty of New Echota – by a single vote. The southern conservative delegation gained an extra 21 votes in the House because they could count their slaves as 3/5ths of a person. Thus, a minority of whites approved a treaty signed by a minority of the tribe that would result in a domestic deployment of troops to deport an entire tribe. They created a false majority to impose white supremacy. American white “democracy” was working exactly the way it was designed to work.

The duly-elected Cherokee leadership appealed to Congress, the Supreme Court, the White House, and the American people. The Cherokees, more literate than the white pioneers, followed the news in our own newspaper, the Cherokee Phoenix, which was typed in our own language.

Wool quickly realized the Cherokees were largely peaceful, and even back in DC, Secretary of War Cass acknowledged that white fears of violent Natives were unfounded. Tennessee was not war-ravaged.

Wool reduced the volunteer militia down to 200 men, presumably weeding out the proto-Proud Boys and white rage rabble. And he sought to protect the Cherokees with his small group of regular enlisted soldiers. For his efforts, Wool was censured by the army for his handling of his duties and the state of Alabama sought a court martial against him.

Brigadier General R. G. Dunlap

Wool was not the only disenchanted general. Brigadier General R. G. Dunlap, a former Tennessee legislator, served under Wool to oversee the remaining 200 Tennessee volunteers. He came to the same conclusions: the Cherokees were the ones who needed protection, and that the treaty was fraudulent. He threatened to resign.

Dunlap preached to his volunteer militia. Working to deport the Cherokees, he said, would “dishonor the Tennessee arms… by aiding to carry into execution at the point of bayonet a treaty made by a lean minority against the will and authority of the Cherokee people.” He then went over Wool’s head and sent letters directly to both Secretary of War Cass and President Jackson, telling them the same: essentially, that obeying orders would dishonor the Tennessee National Guard.

In September, Wool discharged Dunlap from his duties, arguing that the volunteer militia didn’t need someone of his high rank, though Dunlap’s conduct had been exemplary.

The ending

A week later, Wool, contradicting previous policy, allowed the Cherokee National Council to meet, though Secretary of Cass told Wool that no repudiation of the treaty would be tolerated. But the Council repudiated it anyway. Over 2,000 Cherokee leaders signed a statement declaring the treaty fraudulent. In a private conservation with Chief Ross, Wool suspected this was coming – a final opportunity for the Cherokees to make their case to the public. Borrowing a page from Dunlap, he forwarded the statement directly to Cass and Jackson.

President Jackson was enraged. In November, after four months at Fort Cass, Wool wrote to Cass, asking to be reassigned.

The Cherokees sent a counter-letter, saying they wanted Wool to stay, that they needed him for protection from white settlers. Wool stayed, and continued to use his small contingent of troops to protect the very people he was sent to deport.

By the spring of 1837, Martin Van Buren had replaced Andrew Jackson, but continued the policy of ethnic cleansing. Despite the controversy at Cherokee Nation, the Trail of Tears would move forward.

Finally, on July 1, 1837, after a year of tumultuous service, Wool was relieved of his duties. Presumably because he could not find any other willing generals, General Winfield Scott, the Commanding General of the entire US Army, personally went to Fort Cass to oversee the ethnic cleansing of the Cherokees. To get an idea of how pervasive the debate was among white people – and even within the army elite – friends of Scott tried to dissuade him from the immoral mission.

President Van Buren, a close friend of Scott’s, argued, “No state can achieve proper culture, civilization, and progress of safety as long as Indians are permitted to remain.” Today, much of the former Cherokee homeland is represented by Marjorie Taylor Greene.

Wool wasn’t fired. He was reassigned to his previous post as Inspector General. He went on to serve for another 26 years in the US Army, running into similar issues regarding Natives and white pioneer militias in the Northwest in the 1850s. He regularly sought to protect Natives from settlers. In print, he fervently and eloquently blamed massacres and atrocities on the pioneer volunteers, who he explained were motivated by pure greed.

(In the Northwest in the 1850s, Superintendent of Indian Affairs Joel Palmer, who worked alongside Wool, was another who sought to protect Native Americans from ethnic cleansing and genocide. He was fired for his efforts.)

After Wool’s departure, General Scott brought in thousands of enlisted troops and even more thousands of local volunteers – the very men who would take our lands. On the morning of May 26, 1838, they began going door-to-door, cabin-to-cabin, farm-to-farm, rounding up men, women, and children at bayonet point, and marching us into stockades. Behind us, the volunteer militia were visibly stealing our clothes, furniture, and livestock.

Though many accounts of Scott quote his orders to be kind and gentle, everyone knows that a quarter of all Cherokees did not survive the next ten months. The majority died in the stockades at Fort Cass before the journey began. We have the US Army requests for wood for coffins, the majority of which were for children’s coffins.

The cover-up

You’ll have a hard time finding this story in most accounts of General Wool. A National Park Service description of Wool says only that “he took charge of driving the Cherokee Nation west over the ‘Trail of Tears.’” Even an entire book about Wool says little to nothing about his defense of the Cherokees. Wikipedia simply says, “Wool participated in the removal of the Cherokee.” Such erasure and obfuscation has gone on since the events described.

But us Cherokees know the real story. We have not erased it. Generals do revolt.

Sources:

Hinton, H.P. and Thompson, J., 2020. Courage Above All Things: General John Ellis Wool and the US Military, 1812–1863. University of Oklahoma Press.

McMillion, O.A. 2003 “Cherokee Indian Removal: The Treaty of New Echota and General Winfield Scott.” Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 778. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/778

Nance, B.C. 2001. “The Trail of Tears in Tennessee: A Study of the Routes Used during the Cherokee Removal of 1838.” Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation, Division of Archeology.

Sell, G.E. 2003. “Settler Mythology and the Construction of the Historical Memory of the Indian Wars of the Pacific Northwest.” Masters Thesis. University of Northern British Columbia, Department of History.

I read the Wikipedia entry. There is a major gap and this stack would make a great addition to the entry for Wool. I encourage you to go in and edit the entry as part of continuing to enrich our understanding, especially as Wikipedia is such a go to source.

I am grateful for the account and continued growth in my understanding that our current moment of manufactured crises to advance corrupt political goals (again advancing a white Christian nationalist agenda) is a recurrent theme in American history that we need to be more aware of if we are to bend the curve in a new direction.

Just devastating. Thank you for this, Steve