The complicated decline of the Rufous Hummingbird

Spraying Round-up from helicopters and feeder wars hurt, but wildfires may help

For all the dark dusky birds in the Pacific Northwest – gray-bellied Downy Woodpeckers, Song and Fox Sparrows so dark you can’t tell them apart from ten feet away on a cloudy day (which is most days), and nearly-spotless Spotted Towhees – there is a standout: a sparkling orange firecracker, our star, our exploding supernova of energy, the Rufous Hummingbird, brightening up our summers with fierce buzzing wings, a display flight with high-speed skid marks, and a song that sounds like two electric wires touching… touching… and then exploding.

Their population is now in steep decline.

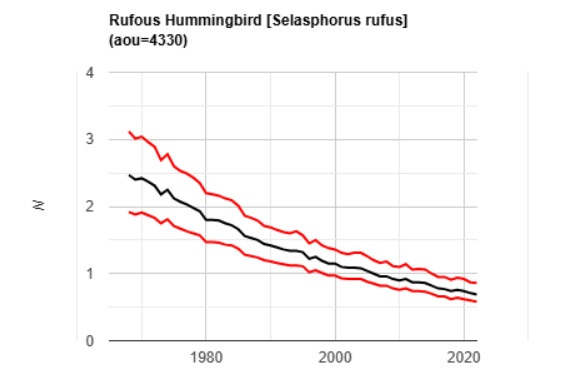

The declines have been detected since at least 1970. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List has moved it from “least concern” to “decreasing” to “near threatened.”

When the Rufous Hummingbird was named “Bird of the Year” by the American Birding Association in 2014, population declines weren’t even mentioned. Instead, they focused on the increase in over-wintering birds along the Gulf Coast and southeastern US.

In their paper, Current contrasting population trends among North American hummingbirds, English et al (2024) report a 65% decrease in Rufous Hummingbirds between 1970 and 2019.

According to Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) data, they declined 43% between 2006 and 2021, which works out to an average annual decline of 3.5% (Jeffrys et al, 2024). The Birds of the World (BOW) species account, using older data, reported slower declines in the past, “These BBS data show significant declines 1980-2004 in: British Columbia (-2.3%/yr); Oregon (-1.1%/yr); Washington (-0.8%/yr). No region shows significant positive trends for this period.” The BBS graph suggests a constant and continuing decline.

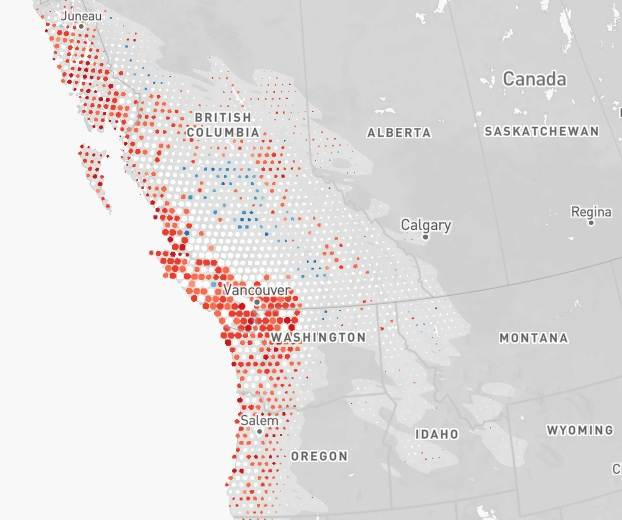

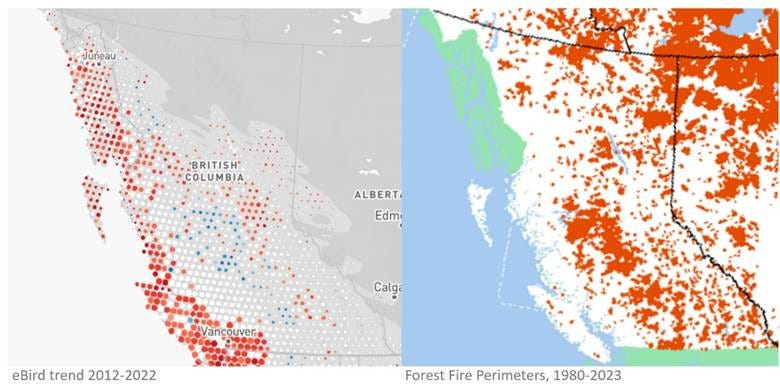

eBird’s trend analysis reports a range-wide decline of 14.5% between 2012 and 2022 (equal to 1.2% per year), and a 19.4% decline (1.9% per year) in Washington state alone. But the eBird trend map illustrates a more complicated story – three of them, actually.

Before we get into the three stories, let’s describe their habitat preferences. In a world of towering forests, Rufous Hummingbirds are looking for flowers, which means they’re looking for open spaces, edges, where the sun shines. Scrubby stream sides, rural edges, timberline meadows, early stage re-growth after fires or logging, old growth forests with a mosaic of trees and openings, and suburbia, especially outskirts with a more rural character.

Here are the three stories:

· They are declining in their core range – along the coast from Alaska to Oregon. This is logging country, sparsely populated. There are no cities along the outer coast with more than 15,000 people.

· They are also declining in suburbia. The hummingbird feeders, ornamental plantings, and open spaces of Vancouver, Victoria, Seattle, Tacoma, Olympia, and Portland are offering no refuge.

· Though a small population (the blue dots are small), they are increasing in interior British Columbia, in the hilly lowlands north of Kamloops, and along the Fraser and Nechako Rivers. And they are holding steady (the white dots) in much of the interior mountains.

The data from eBird tracks reasonably closely to National Audubon’s predicted range shifts under climate change scenarios. This map, under a 3C scenario, predicts decreases along the coast, but increases in the interior, especially in the north. Such northward range shifts are predicted for most species, and indeed have already been documented for hundreds of them.

Now for a deep dive into the three regions, which each tell a different story.

The Coast Ranges: Spraying Round-up from helicopters

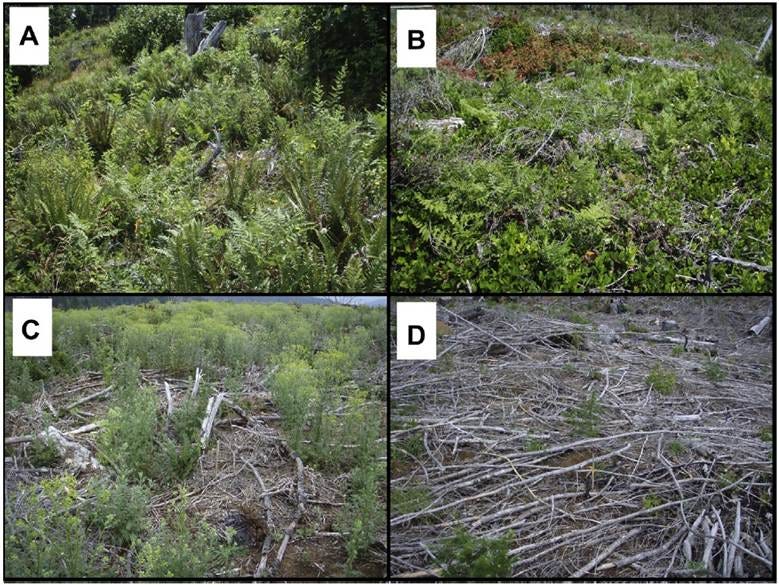

In theory, logging should be good for these birds, opening up meadows with flowers and shrubs during the early stages before the forest grows back. Indeed, the Birds of the World account said there was “no clear explanation for these declines. Biological meaning relative to extent of deforestation unclear, but secondary succession after logging, fires, and highway construction should increase food resources from flowering forbs and shrubs. Further study needed.” And, “Short-term effects of tree-cutting may allow seral flowers to achieve greater abundance than under forest canopy.” That is, logging could be good for them.

This all makes sense if the logging industry wasn’t spraying their clearcuts with herbicides. But they are. This is done to prevent weeds from growing, thus enabling the rapid regrowth of Doug-fir seedlings and other timber harvest species. The herbicides used are glyphosate (essentially Round-up) and similar compounds. To quote from the Oregon State University Extension Service’s educational document (last revised in 2024), Introduction to Conifer Release, “Newly established seedlings can be released from grass and weed competition by applying herbicides from an aircraft or backpack sprayer.” Yes, that means helicopters. Public lands have tighter regulations than private lands, though the hummingbirds depend on both.

From Table 1 of the same document, you’ll learn that “weeds” is an industrial term for broadleaf trees, shrubs, and flowers. The list in the table includes fireweed, salmonberry, elderberry, huckleberry, manzanita, oceanspray, vine maple, thimbleberry, salal, Ceonothus, hazel, alder, bigleaf maple, tanoak, and madrone. The Doug-fir, however, survive the Round-up. “Conifer release” (that link is Wikipedia) is the rather dystopian industrial term for this floral catastrophe.

If you’ve read Finding the Mother Tree by Suzanne Simard, or seen her amazing Ted Talk, your mind and spirit may be screaming now. Because it’s those alders and other “weeds” that share resources with the young Doug-firs through an underground fungal network in order to create an ecologically diverse forest. Her recommendations have only been minimally adapted.

But that’s not the logging industry’s goal. They call them forests, but if you drive along the Oregon, Washington, or British Columbia coast, what you’ll see are tree farms – forests of densely packed trees, all of the same species, all of the same height, growing like a corn field. It’s dark inside. There are no flowers.

So, in logging areas – most of the coastal mountains from BC to Oregon – Rufous Hummingbirds are left with either a glyphosate wasteland or a forest as dense as that faced by Little Red Riding Hood. Also in 2024, other Oregon State researchers, in concert with ornithologists from Canada and the UK, published Jeffrys et al. “Breeding habitat loss linked to declines in Rufous Hummingbirds,” in Avian Conservation & Biology.

They don’t use the clear language I use. There’s no mention of helicopters and the word “herbicide” only shows up three times. You have to know the terms and read between the lines. In the abstract, they focus the hummingbird’s decline on “habitat loss, such as intensive forestry and suppression of early seral habitat, along the Pacific Coast.”

Deeper in the paper they explain, “The majority of habitat suitability declines we detected occurred in areas of stable forest cover… with previously early seral stands undergoing succession to become denser, closed-canopy stands (Phalan et al. 2019). In tandem with succession on federal lands, recent intensification of forestry in the Pacific Northwest (PNW) has likely reduced floral resources and the quality of early seral forest habitat on industrial lands. Previous work in this region has found negative associations between avian species richness, including Rufous Hummingbird abundance, and intensive forestry practices such as herbicide use.”

That previous work includes the following:

· Easton and Martin (1998) The effect of vegetation management on breeding bird communities in British Columbia. They examined the impact of heavy herbicide use in logged areas. They found that bird communities suffered more under herbicide treatment than manual thinning.

· Betts et al (2013) Initial experimental effects of intensive forest management on avian abundance. Focusing on herbicide use in logging along the Oregon coast ranges, they listed the most impacted species as House Wren, Orange-crowned Warbler, Rufous Hummingbird, Wilson’s Warbler, and American Goldfinch. All of those show declines in the Oregon coast ranges.

· Kroll et al (2017) Assembly dynamics of a forest bird community depend on disturbance intensive and foraging guild. Similar to the studies above, they found a clear impact moving from the control site to the most intensive herbicide use post-logging, with bird populations falling 8 to 52%. Rufous Hummingbird seemed to be somewhere in the middle (the graph is difficult to see).

For more on the decimation of the forests of the Pacific Northwest, I highly recommend the book The Golden Spruce by John Vaillant regarding British Columbia, and the podcast Timber Wars regarding Oregon and Washington.

Altogether, this provides a pretty strong explanation for those dark red dots on the eBird trend map from Juneau to Coos Bay.

Suburbia: Competition from Anna’s?

The residential and inhabited rural areas around the Salish Sea, the Puget Trough, and Willamette Valley offer respite from logging. In theory, the open spaces, flowers (both native and ornamental), and even hummingbird feeders of suburbia should provide a happy home for Rufous Hummingbirds.

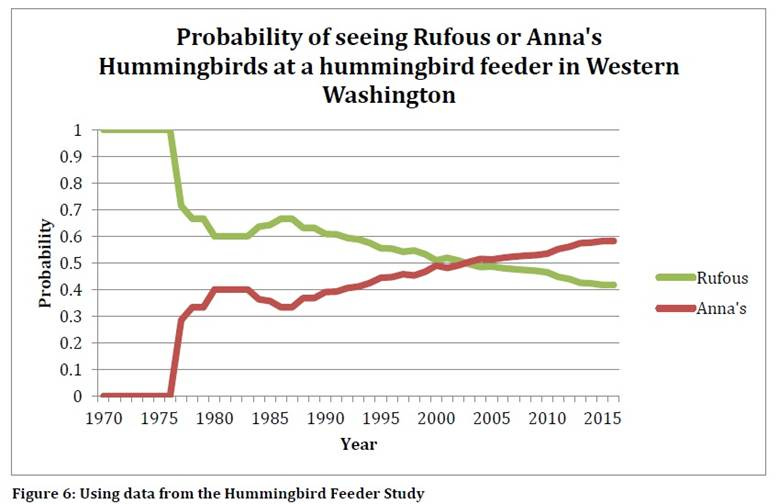

And yet, here in this flower paradise is where we see some of their steepest declines. If you hover over a dot on the eBird trend map, you get the details. From Vancouver to Portland, the declines are similar to the logged coast, averaging about 30% over an 11-yr period, or about 3% per year.

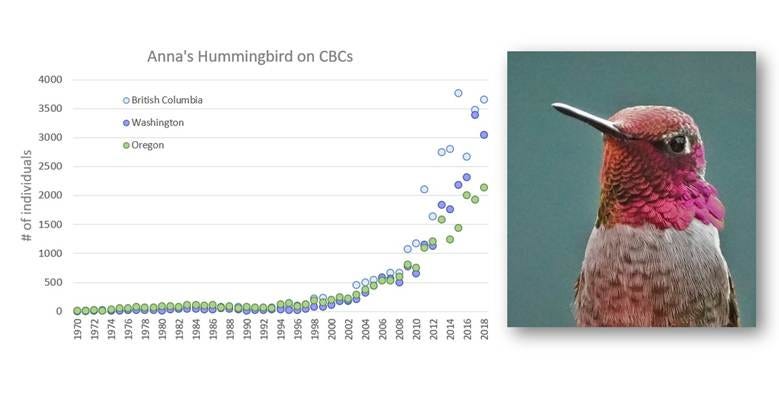

One theory is competition from Anna’s Hummingbirds. Anna’s haven’t always been here. They are among the most notable of the many non-migratory species expanding their ranges north. This was originally due to non-native plantings around human habitations, noted as early as the 1940s in California. They made it to the PNW in the 1960s. Climate change has since been a force multiplier. Christmas Bird Count (CBC) graphs of Anna’s in the PNW now resemble other graphs associated with a warming world: acres burned in Western wildfires, missing sea ice in the Arctic, and the advancement of Black Phoebes, Great Egrets, California Scrub-Jays and others into the PNW.

As recently as 2002, my own Port Townsend CBC did not encounter a single Anna’s. Now, it’s triple digits.

At a hummingbird feeder, Anna’s and Rufous both rate among the most aggressive competitors. In my backyard, they seem to reach a détente, sharing the feeders, but never at the same time, of course. It’s wise to put up several, and in places where they can’t see each other.

I’ve heard of instances, however, where the larger Anna’s is the victor. Near my home in Port Townsend, a friend had a Rufous over-wintering, sharing a feeder with many Anna’s. Barely a week before the CBC, an Anna’s killed the Rufous.

In 2018, Lauren Rowe, an undergrad at UW, wrote Rufous and Anna’s Hummingbird population changes in Western Washington for her senior project. At feeders, she found an increasing trend in Anna’s and a decreasing trend in Rufous. The Rufous, she noted, were decreasing at feeders faster than their overall population decline. This suggests they were avoiding feeders because of Anna’s Hummingbirds. This matches my observations in Port Townsend; they focus more on flowers in yards and prefer more rural areas.

The marked decline of Rufous in metropolitan areas detected by eBird data is no doubt real, but may also reflect a feeder bias. And perhaps newer eBirders miss Rufous feeding in natural contexts, where they are best detected by the sound of their wing buzz, not by not sight. Regardless, it’s pretty clear that Anna’s are more common in more developed areas (which are also increasing), but Rufous are still common in more rural areas.

Because Anna’s are not migratory, and people now feed them through the winter, they establish territories and control hummingbird feeders before the Rufous arrive in spring. Rowe suggests that people who live in rural settings bring in their feeders during the winter to deny Anna’s that home court advantage. I may experiment with that, though in my experience, the newly arriving Rufous manage to negotiate feeder time here.

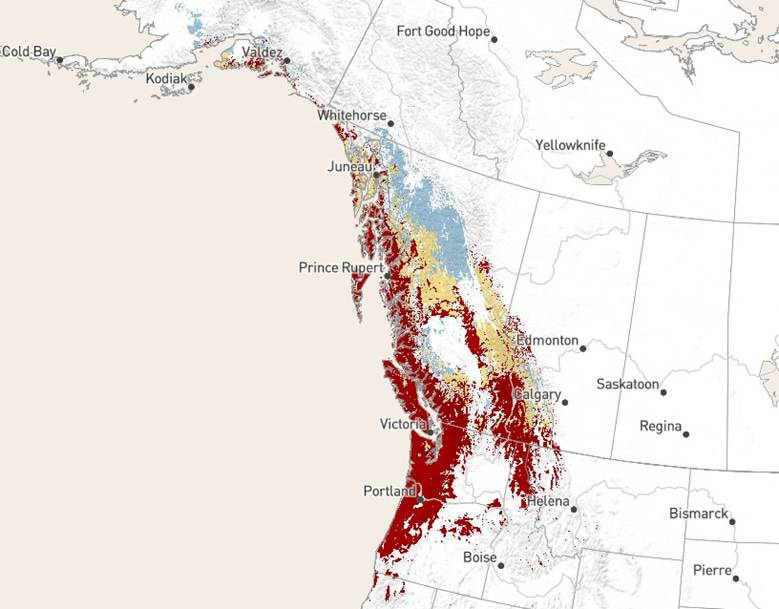

The Interior Mountains: A bird of the flames

A comparison of where Rufous Hummingbirds are increasing and where there is a history of wildfires shows a pretty good match.

This should come as no surprise. After a fire, there is often a profusion of wildflowers, which are part of the early seral stage of regrowth. The increase in fires with climate change is well documented. British Columbia never exceeded 100,000 hectares burned in any year between 1990 and 2002. Since 2003, they’ve tripled and quadrupled that several times, and hit 1.4 million ha in 2018. So there’s a lot of wildflowers coming up, and very few Anna’s in this region. Further north, where the Audubon map predicts they’ll move, they may find more refugia.

Bad news and good news

Rufous hummers winter in central Mexico, mostly on the west slope from Sinaloa to Oaxaca. Increasingly, they are found along the Gulf Coast in the Southeast US as well. An analysis of their winter challenges is beyond the scope of this post.

There are compelling reasons why the stories from their breeding range explain their decline. This fierce sparkplug of a bird is buffeted by wanton habitat destruction in its core range, along the mountains and valleys of the coast; is struggling to maintain a toehold in the metropolitan areas of the inland valleys, fighting with Anna’s, an aggressive interloper itself adapting to habitat modifications and climate change; but is finding potential refuge in the northern interior, where climate change is working to its advantage.

Like most birds, they’ll suffer, but find a way to survive.

My first name is Norwegian for “hummingbird” so I gravitate towards all hummingbird stories. This one was well-researched, well-written and much appreciated!

I enjoy your posts/articles and would like to comment on this one…

Both Anna's & Rufous Hummingbirds nest in our yard, which is located about 1.3 miles due south of the base of Dungeness Spit. Except for when temperatures drop below 20°F, I don't put out feeders. However I do encourage native vegetation, such as orange honeysuckle (Lonicera ciliosa), fireweed (Chamaenerium augustifolium), ocean spray (Holodiscus discolor) and other flowering natives I won't bother listing. Besides nectar (which also attracts insects consumed by hummers as well as other species), these plants provide other benefits. The honeysuckle fruits are consumed by numerous species. The silk in the fireweed seed tufts is used by female hummingbirds in nest construction. Last spring I watched two female Anna's tussling in mid-air over the fireweed—presumably over access to the silk. (I also observe females gathering spider web under the eaves of our house.)

Though I've seen two male Rufous Hummingbirds within about 300 meters of our yard, I've yet to observe a Rufous at our place this year. My anecdotal experience in recent years agrees with the conclusion that they are in decline locally. Thank you for bringing more attention to yet another problem of industrial timber harvest and production methods.